For International Women’s Day this year, here’s a video honouring some great eighteenth-century women!

Tag: 18th century

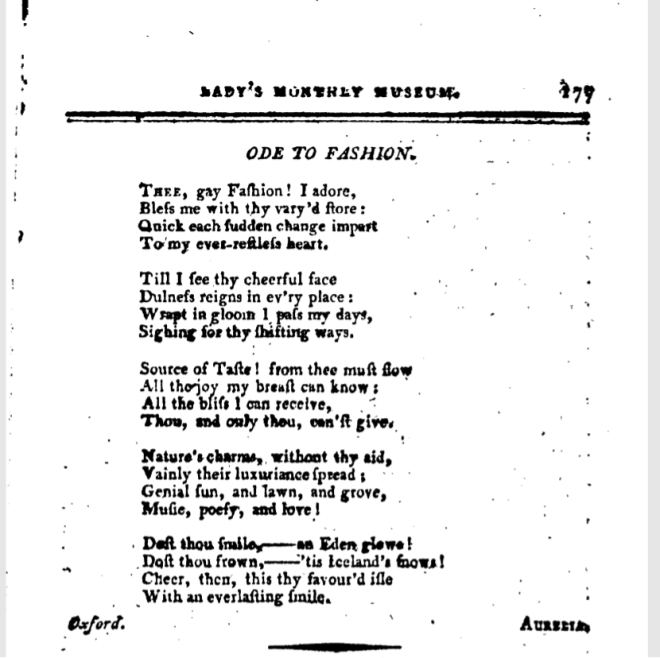

An Ode to Fashion

Because I’ve seen new autumn/winter fashion appearing everywhere, here’s a short poem published in The Lady’s Monthly Museum (March 1800), by ‘Aurelia’ from Oxford!

On this day: 222 years ago, Mary Wollstonecraft gave birth to her daughter Mary

On 30 August 1797, Mary Wollstonecraft gave birth to her daughter, the future Mary Shelley.

To mark this date, here are some accounts of her life and death.

In his Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1798), her husband William Godwin writes:

‘She was taken in labour on Wednesday, the thirtieth of August. […] She was so far from being under any apprehension as to the difficulties of child-birth, as frequently to ridicule the fashion of ladies in England, who keep their chamber for one full month after delivery. For herself, she proposed coming down to dinner on the day immediately following. She had already had some experience on the subject in the case of Fanny; and I cheerfully submitted in every point to her judgment and her wisdom. She hired no nurse. Influenced by ideas of decorum, which certainly ought to have no place, at least in cases of danger, she determined to have a woman to attend her in the capacity of midwife. […] At five o’clock in the morning of the day of delivery, she felt what she conceived to be some notices of the approaching labour. Mrs. Blenkinsop, matron and midwife to the Westminster Lying-in Hospital, who had seen Mary several times previous to her delivery, was soon after sent for, and arrived about nine. During the whole day Mary was perfectly cheerful. Her pains came on slowly; and in the morning, she wrote several notes, three addressed to me, who had gone, as usual, to my apartments, for the purpose of study. About two o’clock in the afternoon, she went up to her chamber, — never more to descend.’ (pp. 178-180)

Her (occasional) acquaintance Elizabeth Inchbald mentions Wollstonecraft’s labour and death in a letter:

‘She was attended by a woman, whether from partiality or economy I can’t tell — but from no affected prudery I am sure. She had a very bad time, and they at last sent for an intimate acquaintance of his, Mr. Carlisle, a man of talents. He delivered her; she thanked him, and told him he had saved her life: he left her for two hours — returned, and pronounced she must die. Still she languished three of four days. This is the account I have heard, but not from him [Godwin]; he has written to me several times since; but they are more like distracted lines than any thing rational.’ (Memoirs of Mrs. Inchbald, London: Bentley, 1833, pp. 14/15)

Mary Shelley, who only knew her mother from her writings, portraits, and her gravestone, later wrote about her:

‘The writings of this celebrated woman are monuments of her moral and intellectual superiority. Her lofty spirit, her eager assertion of the claims of her sex, animate the “Vindication of the Rights of Woman;” while the sweetness and taste displayed in her “Letters from Norway” depict the softer qualities of her admirable character. Even now, those who have survived her so many years, never speak of her but with uncontrollable enthusiasm. Her unwearied exertions for the benefit of others, her rectitude, her independence, joined to a warm affectionate heart, and the most refined softness of manners, made her the idol of all who knew her. Mr Godwin was not allowed long to enjoy the happiness he reaped from this union. Mary Wollstonecraft died the 10th September 1797, having given birth to a daughter, the present Mrs. Shelley.’ (‘Memoirs of William Godwin’, in Caleb Williams, (London: Bentley, 1831), p. ix)

And finally, some of Mary Wollstonecraft’s own thoughts on motherhood:

‘To be a good mother — a woman must have sense, and that independence of mind which few women possess who are taught to depend entirely on their husbands. […] Females, it is true, in all countries, are too much under the dominion of their parents; and few parents think of addressing their children in the following manner, though it is in this reasonable way that Heaven seems to command the whole human race. It is your interest to obey me till you can judge for yourself; and the Almighty Father of all has implanted an affection in me to serve as a guard to you whilst your reason is unfolding; but when your mind arrives at maturity, you must only obey me, or rather respect my opinions, so far as they coincide with the light that is breaking in on your own mind.’ (A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, pp. 233/237)

Reflections of the Revolution: Elizabeth Inchbald’s ‘The Massacre’ (1792)

During the French Revolution in 1789, it must have been almost impossible for a writer in Britain not to engage with politics. Any examination of literature of this time shows that the French Revolution influenced novelists, poets, diarists, painters, and generally artists of any kind. At first glance, however, female playwrights appeared reluctant to engage with the French Revolution in particular. Perhaps because it was such a politically and socially divisive event, they avoided commenting in detail or taking a side. None of the female-authored plays staged during that time deal with the Revolution as a main subject.

The only play that is unequivocally about the French Revolution is Inchbald’s The Massacre (1792). It was, however, never staged or even published during her lifetime. While the massacre of the title supposedly refers to the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre in France in 1572, it is very obvious to the reader that Inchbald is actually writing about the September massacres of 1792. The timing and setting of the play, as well as the fact that the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre is hardly ever mentioned, heavily imply that the story is really about contemporary events in France. The September massacres, lasting from September 2 to September 6 1792, were a period of unprecedented violence during the French Revolution. Encouraged by rumours of a counter-revolutionary plot, mobs attacked prisons in Paris, and executed prisoners, often finding them guilty of treason in impromptu courts. By the end of the massacres, over a thousand people had become victims of this violence. It was one of the events that contributed majorly to the opposition against the Revolution in other countries, especially in Britain.

It appears that Inchbald never intended this play for the stage, but wrote it as a closet drama. It has only three acts, making it easier for people to read through at home, there is very little action and a great deal of dialogue, which would not make it ideal for a theatrical production. There are only two female roles, and one of them is practically non-speaking. Given how many roles Inchbald usually wrote for actresses, suddenly depriving them of good parts in this play is out of character. But for a closet play this character division makes more sense – Inchbald would not be concerned about writing roles for her colleagues in a play that was never going to reach the stage, and female readers at home would find it easier to read through the play with family members or a friend. The non-public nature of The Massacre accounts for how much it differs from Inchbald’s other works. It is also, of course, a tragedy, and therefore stands out from the comedies which were her more usual genre.

The Massacre is a departure for Inchbald not only in its form, but also in its tone and characterisation. She very rarely writes about anything in an entirely serious tone, and even serious subjects in other plays are frequently treated with a dry, black humour. But in this instance the whole play is entirely serious. Clearly she perceived it as so important that she could not soften or mitigate its impact in any way. In her Advertisement for The Massacre, Inchbald quotes a statement by Horace Walpole about one of his own plays:

‘The subject is so horrid, that I thought it would shock, rather than give satisfaction, to an audience. Still I found it so truly tragic in the essential springs of terror and pity, that I could not resist the impulse of adapting it to the scene, though it never could be practicable to produce it there’.[1]

Inchbald stresses how applicable this quote is to her own work, and states her belief that it will explain why The Massacre has not been performed. Walpole’s quote also serves as a kind of warning – if the reader was expecting one of Inchbald’s usual comedies, this was far from being one.

And the play itself certainly deserves this warning. The play starts with Madame Tricastin fearing that her husband has been killed on a visit to Paris, and this fear accompanies her throughout the rest of the play, until, tragically, he actually survives and she dies instead. This constant threat of violence very effectively captures the atmosphere during the September massacres, in which events must have seemed unpredictable and deaths occurred frequently. No doubt it also reflected the mood in Britain, where the volatile situation in Europe caused concern and uncertainty. The threat of mob violence was an especially present one for someone as closely associated with the theatre as Inchbald, since theatre audiences had a history of becoming violent to express their displeasure. Both Drury Lane and Covent Garden had seen riots in 1744 and 1763 respectively, and there were to be more theatre riots at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Inchbald’s representation reflects these anxieties, at a time when they were fuelled by the violence of the French Revolution, and by events such as the Priestley Riots (1791) which brought the fear of hostile crowds home to England.[2]

From the list of characters, it may appear that The Massacre is a very male-centred play, and in comparison with Inchbald’s other works it certainly is. Madame Tricastin is the only female character with any significant dialogue and stage time. However, she plays a very important role. Madame Tricastin is a constant reminder of how one person’s actions affect others. She does this first by telling Tricastin they should leave the country rather than try to fight; when he objects, she reminds him that he has a family who would be devastated if he died in the fighting. She does it again in the second Act, preventing Tricastin from killing himself in despair at being surrounded (I, 1, and II, 1, respectively). In the last Act, Madame Tricastin is herself killed by the mob; the soldiers who witness this are so affected by her death that they do not engage in combat but instead guard her corpse from being mistreated. She becomes a powerful visual symbol of the consequences of violence. The shock of seeing her dead body prompts the character Glandeve to reaffirm the need for reason and humanity, and his final speech almost reads like her funeral service:

‘the good (of all parties) will conspire to extirpate such monsters from the earth. It is not party principles which cause this devastation; ’tis want of sense — ’tis guilt — for the first precept in our Christian laws is charity — the next obligation — to extend that charity EVEN TO OUR ENEMIES.’ (III, 2)

Madame Tricastin’s fate helps the male characters and the audience to determine what is morally right. There is no denying that this representation casts women in a much more passive role, and especially in the case of Madame Tricastin recalls the way Burke wrote about Marie Antoinette – as a virtuous, feminine mother figure who is the victim of the uncivilised mob.[3] Perhaps Inchbald felt that the form of the tragedy called for such a female character. It is after all very difficult to imagine one of her usual witty heroines in Madame Tricastin’s situation. Their sarcasm, wit, skilful manipulation of social settings, and knowledge of gender expectations would be of no use to them here.

There is also a suggestion that Madame Tricastin has been made more helpless than she already is by her society’s gender expectations. When her husband Eusèbe decides that flight is impossible and that they should try and fight their attackers, his friend suggests that Madame Tricastin should have a weapon as well:

‘Menancourt: Give her an instrument of death to defend herself — our female enemies use them to our cost.

Eusebe: No, by Heaven! so sacred do I hold the delicacy of her sex, that could she with a breath lay all our enemies dead, I would not have her feminine virtues violated by the act.’ (II, 1)

His refusal to even consider that his wife should be able to defend herself means that once she is separated from him, she has no way to fight back. Clearly women are not unable to use weapons, as Menancourt specifically mentions other women who do just that. Her ‘delicacy’ and ‘feminine virtues’ are of no help at all to her, since they cannot protect her. Inchbald is suggesting that trying to be too delicate and self-sacrificial, and caring too much about what other people define as virtuous, is harmful to women. However, Madame Tricastin really is in a position where there is no good way out for her. Complying with her husband’s wish that she should be delicate and feminine means she is helpless. But if she had decided to ignore him and fight back, she would have lost her reputation, and with it, her femininity. Faced with the decision between her life and her virtue, she prefers to die, and that gives us a powerful insight into the importance late eighteenth-century society placed on female virtue.

The Massacre is an interesting development in Inchbald’s writing career. Not only was she writing in a genre she had not attempted before, but she also engages with contemporary politics in a new way. This is not a consequence of either her changing personal opinions or a move towards becoming a writer of tragedies. After The Massacre, Inchbald returned to writing the comedies she was known for, producing Every One Has His Fault and Wives as they Were, which feature some of her most cynical, cutting humour. If it is not therefore the case that she wanted to change her genre of choice or her portrayal of women, it must be that the subject matter simply called for a different approach.

Notes:

[1] Elizabeth Inchbald, The Massacre, in Memoirs of Mrs. Inchbald, Including her Familiar Correspondence with the Most Distinguished Persons of her Time, ed. by James Boaden (London: Bentley, 1833), p. 357.

[2] See Marilyn Butler, Romantics, Rebels and Reactionaries (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981), p. 47.

[3] Edmund Burke, Reflections on the Revolution in France (London: Dodsley, 1790), p. 78.

Really enjoyed speaking at the Women & the Arts in the Long Eighteenth Century conference at Sheffield University on International Women’s Day!

Lovely report by conference organiser Hannah Moss here: http://www.bars.ac.uk/blog/?p=2317

Marriage, She Wrote: Elizabeth Inchbald’s Wives as they Were, and Maids as they Are

The importance of marriage as a theme in comedies of the eighteenth century cannot be exaggerated. Because of the established difference between the public and private spheres, and women’s supposed suitability to speak about more domestic concerns, many if not all plays written by women during the late eighteenth century feature and deal with relationships to some degree. Marriage is of course the most common feature, as comedies traditionally end with at least one wedding.

Given the heavy reliance on marriage as a driving force of the plot, and the romantic concerns of the characters, women’s comedies are frequently criticised for being sentimental or frivolous. Misty G. Anderson comments that, ‘At the level of content, marriage stories contrasted with the heroic themes of “great” literature, and at the level of popular function, their status as mere commercial entertainment opposed an abstract and masculine category of timeless art’(i). In other words, their writing about marriage put female playwrights into a literary category which automatically denoted their work as less valuable. Anderson rightly opposes this category with the ‘masculine’ ideal of art dealing with greater human concerns, gendering the domestic comedy as female, and, therefore, less important. However, while it is easy to ridicule the at times over-the-top value which is placed on marriage in these comedies, it is important to remember that for many women, being married really was one of their concerns in life. It was vital not only socially, but also financially, especially for middle-class women who were prevented from learning a trade, but would also not inherit enough money from their family to live comfortably on their own. Elizabeth Inchbald in particular often emphasises the financial aspects of marriage.

Her Wives as they Were, and Maids as they Are (1797) (ii) centres around two interwoven plots. Firstly, Sir William Dorrillon returns from India to visit his daughter Maria, who has not seen him since she was a child. Maria Dorrillon is one of the ‘Maids’ of the title; she is ‘modern’, outgoing, witty, and has a group of suitors she flirts with but doesn’t take seriously. She is described as a ‘heedless woman of fashion’ (1/1) and Dorrillon is extremely dissatisfied with his daughter’s character.

The second plot concerns Lord and Lady Priory. Lady Priory is a ‘wife as they were’. She is under the strict control of her husband, who refuses to let her leave the house, talk to other women, and sometimes even locks her in her room (1/1).

One of the main themes of the play is the marriage market. Through Maria, Inchbald explores the economic realities facing a single woman during this period. Maria has a number of financial problems: her father is absent and cannot support her, she has borrowed money from friends in the past and therefore cannot ask them for more help, and she likes gambling without being very successful at it. Consequently, she ends up in debtor’s prison in the last act of the play, and is only released when Dorrillon offers to pay her debts and, in the process, is revealed to be her father. Hearing about Maria’s gambling debts, her friend Lady Mary suggests: ‘Why don’t you marry, and throw all your misfortunes upon your husband?’ Maria replies: ‘Why don’t you marry? For you have as many to throw’; to which Lady Mary retorts that it would make better financial sense for Maria to marry, as her suitor Sir George earns ten thousand pounds a year (1/1). Marriage is not a question of personal preference for them; they do not expect to choose a husband based on affection or matching personalities, but strictly on economic considerations. The scene in the debtor’s prison brings about a complete change of tone in the play. The revelation that Mandred (the pseudonym Sir Dorrillon uses) is her father causes Maria to undergo a significant transformation. Whereas before she is assertive, witty, and never afraid to contradict either Mandred or others, after that scene her lines are reduced to three sentences until the end of the play. With one of these sentences she hushes Lady Mary because Lord Priory is about to speak. The second sentence is a last attempt to regain her former independence: Sir George asks her (once again) if she will marry him. She replies, ‘No – I will instantly put an end to all your hopes’ (5/4). What sounds like quite a resolute refusal is instantly contradicted and reinterpreted by her father, who tells Sir George that Maria has consented to marry him after all. When George asks Maria ‘And what do you say to this?’ , she speaks the last words of the play: ‘Simply one sentence – A maid of the present day shall become a wife like those – of former times'(5/4).

Her financial situation, made very real by her stay in the debtor’s prison, convinces Maria of the necessity of marriage. Whereas previously she had been able to joke about marrying a wealthy suitor, it suddenly becomes her only option; she is subdued and literally loses her ability to see marriage as a joke, becoming almost speechless. Marrying Sir George is an exchange of her freedom and wit for financial security, which Inchbald makes abundantly clear by having her characters state exactly how much money George is worth earlier in the play. His wealth is what compensates her, and it is unlikely she would have chosen him if he could not offer her the security of money: ‘Maria Dorillon’s actions in the marriage market are therefore founded on the assumption of equal compensation. A woman only subordinates herself to a man if she is sure of adequate recompense in the institution of marriage.’ (iii)

The other representation of marriage in Wives as they Were, and Maids as they Are is no less pessimistic. It is based on the idea that marriage was a much more serious and strict affair in earlier times, in which wives were completely under the control of their husband.

The embodiment of the wife of former times is of course Lady Priory – arguably the most interesting character in the play. At first she may strike the reader as rather dull, since she appears to confirm too much to the stereotype of the obedient wife. She hardly speaks, takes no part in the gambling, drinking, and socialising that occurs in the play, and spends most of her time in her room. Because such submissiveness is very uncharacteristic for a woman in a comedy play, it is reasonable to assume that the audience would have wanted her to break out of her silence and become more assertive; in this regard, however, Inchbald goes against comic convention: the dramatic rebellion against Lady Priory’s abusive husband, which the audience might expect, never comes. As Anderson remarks, ‘Comic logic all but demands that the jealous Lord Priory be taught a lesson when his oppressed wife bursts forth into a wider community, where she can escape into the arms of a worthier man. This plot, however, never emerges, in spite of a string of opportunities for Lady Priory’s revenge.’ (iv)

From a dramatic point of view, Lady Priory’s plotline is profoundly unsatisfying. Why did Inchbald decide to give her this story, and not one that would have been more accessible and more gratifying to her audience? The environment Lady Priory lives in simply does not allow for such an easy solution. The ‘worthier man’ never actually materialises; Bronzely, who develops an attachment to Lady Priory, and tries to run away with her, is a notorious rake and turns the potentially romantic act of eloping together into an attempted kidnapping and rape. He is also clearly attracted to her unavailability, which he sees as a challenge, rather than her actual person. She demands that he return her to her husband, which he eventually does. This demand may be interpreted as a rather unsatisfying return to the status quo, but ironically it is during this scene, when she has just been abducted by Bronzely, that Lady Priory changes. It is a subtle change; and it is not expressed in a grand gesture or great speech, but in a quiet, very domestic way. When Bronzely tries to frighten her by emphasising her vulnerability, ‘Lady Priory, you are in a lonely house of mine, where I am sole master’, the stage direction has her respond like this: ‘Lady Priory calmly takes out her knitting, draws a chair, and sits down to knit a pair of stockings’ (5/1). Her refusal to be scared, or even to actually react to him, suddenly puts her in a powerful position. She abruptly raises her status, which completely confuses Bronzely. She notices, and makes her position even stronger by pointing out his own vulnerability: ‘Ah! did I not tell you, you were afraid? ‘Tis you who are afraid of me’ (5/1). Bronzely has expected her to play a part, that of the damsel in distress who needs to be rescued; she refuses, and thus confuses both him and the narrative.

Her strategy of silent (or almost silent) resistance continues in the last act of the play. While she returns to Lord Priory and marriage, she does not say what he wants her to say anymore. When he asks her to declare that she hates Bronzely and loves her husband, she stays speechless (5/4). This does not, of course, amount to the ‘revenge’ the plot demands, but it is significant. Lady Priory recognises that she cannot leave her marriage without inviting consequences that would make her situation worse, and so she decides to stay and play the part of the silent wife her husband demands of her. But now she uses this very demand for silence against him by refusing to say what he wants to hear. The only substantial statement she makes about her marriage confirms that this adherence to traditional gender roles is indeed a choice: ‘to the best of my observation and understanding, your sex, in respect to us, are all tyrants. I was born to be the slave of some of you – I make the choice to obey my husband’ (4/2). She sees that her situation would not be improved by choosing another man, and she does not have the choice to choose no man at all, because that would leave her without any financial and social support. The only thing she really has control over, is her speech, and she uses the lack of it very effectively to confuse the men who are in control of her. In this light, perhaps Maria’s lapse into silence at the end of the play may be interpreted as a similar strategy: she has also recognised the necessity of conforming to the status quo of marriage and resorts to Lady Priory’s silent resistance.

The strategies used by both the characters and their playwright are remarkably similar. Inchbald makes her play conform to the traditional conventions of comedy in terms of form, but there is a hidden rebellious strain that undercuts the play’s surface plot of the necessity of marriage. This results in a play that is, formally and in terms of setting, a domestic comedy, but which is not actually very funny. The expected marriage ending reads more like a sad ending than a happy one, and the audience is left disappointed at some level with the actions of the characters. Comedy is shown as unable to alleviate the reality of women who have to choose marriage out of financial necessity, and Maria’s wit ultimately fails her. Anderson succinctly characterises Inchbald’s decision to make the women silent and serious at the end of her play as an example of her dark humour: ‘Perhaps the final joke of the play is that there is no joke that can moderate the power of husbands and fathers.’ (v)

Notes:

(i) Misty G. Anderson, Female Playwrights and Eighteenth-century Comedy: Negotiating Marriage on the London Stage (New York: Palgrave, 2002), p. 30.

(ii) Elizabeth Inchbald, Wives as they Were, and Maids as they Are (London: Robinson, 1797)

(iii) Daniel, O’Quinn, ‘”Scissors and Needles”: Inchbald’s Wives as They Were, Maids as They Are and the Governance of Sexual Exchange’, in Theatre Journal, No. 51 (Summer 1999), 105-125, p. 120.

(iv) Misty G. Anderson, Female Playwrights and Eighteenth-century Comedy: Negotiating Marriage on the London Stage (New York: Palgrave, 2002), p.196.

(v) Misty G. Anderson, Female Playwrights and Eighteenth-century Comedy: Negotiating Marriage on the London Stage (New York: Palgrave, 2002), p. 192.

Friday Fact!

Hannah Cowley was attending the theatre, and remarked about the play, ‘Why, I could write as well myself.’ Her husband laughed at this, and in response she wrote her first play The Runaway. It was written and sent off to David Garrick within a couple of weeks, and staged at Drury Lane in 1776, running for seventeen performances.

- See British Women Poets of the Romantic Era, an Anthology, 2001, ed. by Paula R. Feldman. Baltimore & London: Johns Hopkins University Press

‘A woman’s lively laugh’

Summary, excerpt, and illustrations of Hannah Cowley’s 1779 comedy Who’s The Dupe?

From The Dramatic Souvenir: Being Literary and Graphical Illustrations of Shakespeare and Other Celebrated English Dramatists; Embellished with Upwards of Two Hundred Engravings on Wood.

Printed by Charles Tilt, 86 Fleet Street, London, 1833.

Friday Fact!

Sophia Lee (1750-1824) started writing while visiting her father in debtors’ prison. John Lee, an actor, was frequently in debt and struggled to support his family. Sophia’s play The Chapter of Accidents was performed in 1780, and her income enabled her to open a school for girls.

Friday Fact!

After giving up playwriting, Mariana Starke (1761/2 – 1838) became a renowned travel writer, publishing Letters from Italy between the Years 1792 and 1798, containing a View of the Revolutions in that Country in 1800, followed by Travels on the Continent (1820) and Travels in Europe (1828). She used a system of exclamation marks (!!!) to rate the quality of recommended tourist attractions and hotels, a forerunner of today’s star rating system.